Photo by Raphael Schaller on Unsplash

CockroachDB JDBC Driver: Part II - Design and implementation Details

A detailed design description of the CockroachDB JDBC driver

In this second article, we'll take a closer look at the design and implementation of the custom-made CockroachDB JDBC driver. See Part I for an introduction to the driver.

Article series on the JDBC driver:

Overview

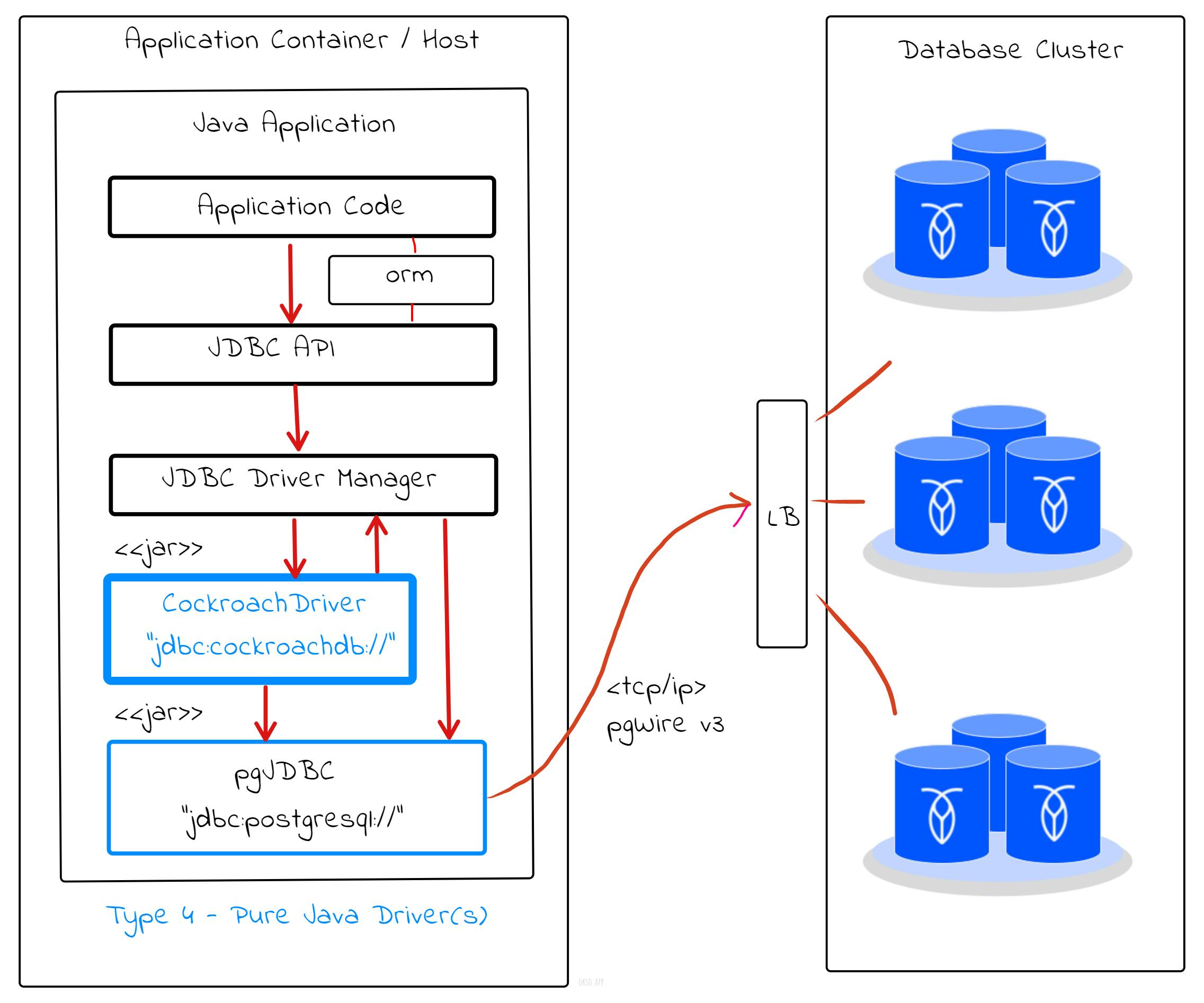

The CockroachDB JDBC driver wraps the PostgreSQL JDBC driver (pgjdbc) which must also be on the app's classpath. There are no other dependencies besides SLF4J for which any supported logging framework can be used.

It works by the JDBC Driver accepting a unique URL prefix jdbc:cockroachdb to separate itself from jdbc:postgressql. When the driver is asked to open a connection (typically by the connection pool), it passes the call forward to pgJDBC and then wraps the connection in a CockroachDB connection proxy with a custom interceptor (invocation handler). The driver delegates all calls to the underlying pgJDBC driver and does not interact directly with the database itself at any point.

Internal Retries

One of the driver features includes internal retries in contrast to application-side or client-side retries which is the common option. It works by the driver wrapping each JDBC connection, statement and result set in a dynamic proxy and interceptors capable of detecting and retrying aborted transactions, warranted that the SQL exceptions are of a qualified type. The qualifying exception types are of two main categories: Serialization Conflicts and Connection Errors.

Serialization Conflicts

The JDBC driver can optionally perform internal retries of failed transactions due to serialization conflicts denoted by the 40001 state code. Serialization conflict errors are safe to retry by the client, or in this case by the driver. Safe, in terms of not producing duplicate side effects since the transaction was rolled back.

This type of error is more likely to manifest in databases running with serializable transaction isolation (1SR), in particular for contended workloads subject to read/write and write/read conflicts.

There are however more limitations with driver-level retries than application-level. See the implementation section further below for more details.

Connection Errors

The JDBC driver can also perform internal retries on connection errors denoted by any of the 08001, 08003, 08004, 08006, 08007, 08S01 or 57P01 state codes. Connection errors during in-flight transactions are generally safe to retry, but there is a potential for duplicate side effects if the SQL operations performed are non-idempotent like INSERTs or UPDATEs with increment operations (UPDATE x set y=y-1).

This could happen for example if a transaction commit was successful but the response back to the client was lost due to a connection failure. In that case, the result is ambiguous and the driver can't tell if the transaction was successfully committed or rolled back.

Retry Implementation

Transaction conflicts and connection errors can surface at read, write and commit time which means there are retry interceptors wrapped around the following JDBC API artefacts:

java.sql.Connectionimplemented by

CockroachConnectionproxied by

ConnectionRetryInterceptor, retries oncommit()

java.sql.Statementimplemented by

CockroachStatementproxied by

StatementRetryInterceptor, retries on write operations

java.sql.PreparedStatementimplemented by

CockroachPreparedStatementproxied by

PreparedStatementRetryInterceptor, retries on write operations

java.sql.ResultSetimplemented by

CockroachResultSetproxied by

ResultSetRetryInterceptor, retries on read operations

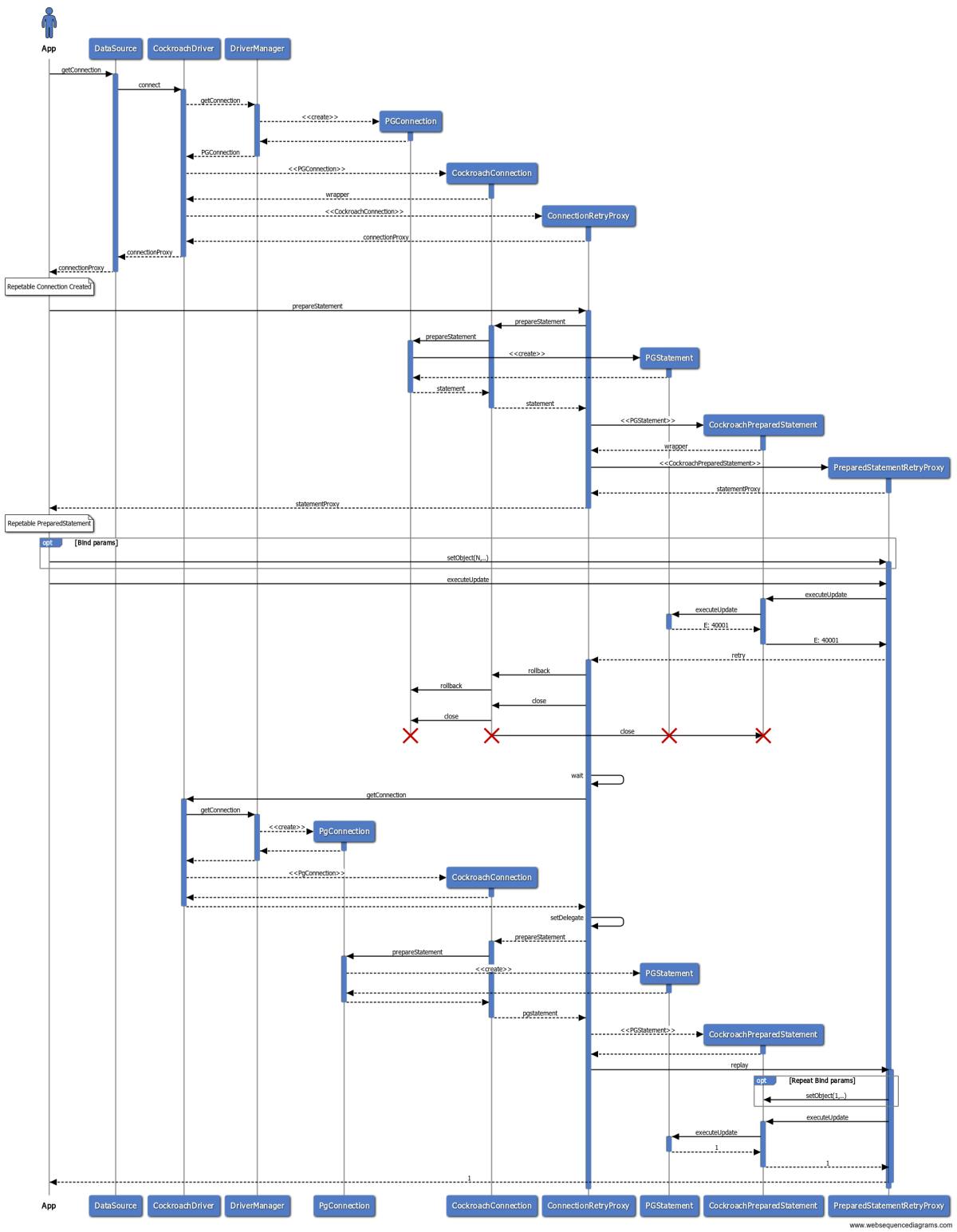

Retries are possible by recording most JDBC operations during an explicit transaction (autoCommit set to false). If a transaction is aborted due to a transient error it will be rolled back and the connection is closed. The recorded operations are then repeated on a new connection delegate while comparing the results against the initial transaction attempt.

If the results observed by the application client are in any way different (determined by SHA-256 checksums), the driver is forced to give up the retry attempt to preserve a serializable outcome towards the application, still waiting for completion.

To illustrate:

try (Connection connection

= DriverManager.getConnection("jdbc:cockroachdb://localhost:26257/jdbc_test?sslmode=disable") {

try (PreparedStatement ps = connection.prepareStatement("update table set x = ? where id = ?")) {

ps.setObject(1, x);

ps.setObject(2, y);

ps.executeUpdate();

}

}

In this example, assume the executeUpdate() method throws a SQLException with state code 40001. This exception is caught by the retry interceptor which will roll back and close the current connection, then repeat the recorded operations on a new connection delegate and hope for a different interleaving of other concurrent operations that allow for the transaction to complete.

From the perspective of the application, the executeUpdate() operation will block until this process is either successful or considered futile, in which case a separate SQLException is thrown with the same state code.

Limitations of driver-level retries

By contrast, when using application-level retries you would typically need to apply retry logic. Something like the following:

int numCalls=1;

do {

try {

// Must begin and commit/rollback transactions

return businessService.someTransactionBoundaryOperation();

} catch (SQLException sqlException) { // Catch r/w and commit time exceptions

// 40001 is the only state code we are looking for in terms of safe retries

if (PSQLState.SERIALIZATION_FAILURE.getState().equals(sqlException.getSQLState())) {

// handle by logging and waiting with an exponentially increasing delay

} else {

throw sqlException; // Some other error, re-throw instantly

}

}

} while (numCalls < MAX_RETRY_ATTEMPTS);

This type of logic fits well into an AOP aspect with an around advice (or interceptor in JavaEE), weaving in between the caller and transaction boundary (typically a service facade, service activator, or web/API controller).

Application-level retries always have a higher chance of success over driver-level because the application logic is applied in each repeat cycle. For example, if you are checking for a negative account balance in the app code, then it may cancel out additional writes based on the value read when the operation is repeated. Neither the JDBC driver nor the database has any visibility to the application logic, which means that a retry attempt can only succeed if all previously observed outcomes are identical to the new ones.

The practical use of driver-level retries is therefore more narrow for common read/write and write/read conflicts, in which case client-side retries are the preferred approach.

Implicit SELECT FOR UPDATE rewrites

The JDBC driver can optionally append a FOR UPDATE clause to qualified SELECT statements.

A SELECT query qualifies for a rewrite when:

It's not part of a read-only connection

There are no aggregate functions (max, min, avg, etc.)

There are no distinct or GROUP BY operators

There are no internal CockroachDB schema references

A SELECT .. FOR UPDATE will lock the rows returned by a selection query such that other transactions trying to access those rows are forced to wait for the transaction that locked the rows to finish. These other transactions are effectively put into a queue based on when they tried to read the value of the locked rows.

Notice that this does not eliminate the chance of serialization conflicts (which can also be due to time uncertainty) but will greatly reduce it. Combined with driver-level retries, this can eliminate the need for app-level retry logic for some workloads.

The following example shows a write skew (G2-item) scenario which is prevented by CockroachDB serializable isolation:

| T1 | T2 |

| begin; | begin; |

| select * from test where id in (1,2); | |

| select * from test where id in (1,2); | |

| update test set value = 11 where id = 1; | (reads 10,20) |

| update test set value = 21 where id = 2; | |

| commit; | |

| commit; --- "ERROR: restart transaction.." |

Running the same sequence with FOR UPDATE:

| T1 | T2 |

| begin; | begin; |

| select * from test where id in (1,2) FOR UPDATE; | |

| select * from test where id in (1,2) FOR UPDATE; | |

| -- blocks on T1 | |

| update test set value = 11 where id = 1; | |

| commit; | -- unblocked, reads 11,20 |

| update test set value = 21 where id = 2; | |

| commit; |

The initial read in T1 will lock the rows and T2 is forced to wait for T1 to finish. When T1 has finished with a commit, the read in T2 is reflecting the write of T1 and not that of T2 at the initial read timestamp. The T2 read is effectively pushed into the future with the desired effect of these operations resulting in a serializable transaction ordering, allowing for both to commit.

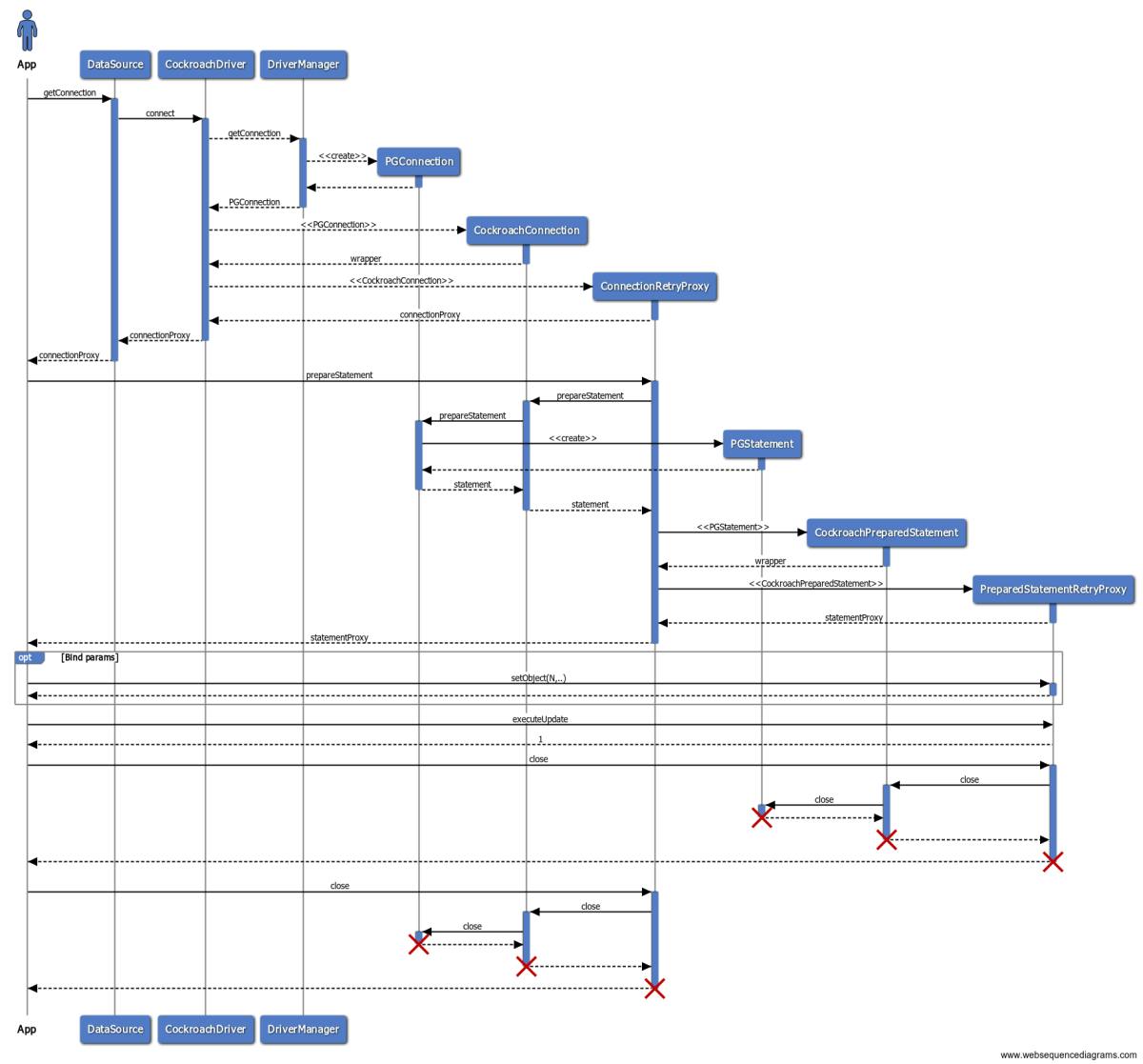

Sequence Diagrams

The driver concepts are illustrated with sequence diagrams using https://www.websequencediagrams.com.

Happy Path

This diagram illustrates executing a single update with a happy outcome, equivalent to:

try (Connection connection

= DriverManager.getConnection("jdbc:cockroachdb://localhost:26257/jdbc_test?sslmode=disable") {

try (PreparedStatement ps = connection.prepareStatement("update table set x = ? where id = ?")) {

ps.setObject(1, x);

ps.setObject(2, y);

ps.executeUpdate();

}

}

Unhappy Path

This diagram illustrates executing the same single block with an unhappy outcome, equivalent to:

Conclusion

This article discusses the design and implementation of a custom-made CockroachDB JDBC driver, which wraps the PostgreSQL JDBC driver and provides features such as internal retries for serialization conflicts and connection errors. The driver also uses driver-level retries and SELECT FOR UPDATE rewrites to reduce the chance of serialization conflicts in a transaction. Sequence diagrams are provided to illustrate the process.